How To Handle Workplace Microaggressions

Picture this: You’ve graduated from school and landed a fantastic new job. Every day, you walk into the office confident in your abilities and eager to prove yourself. For the most part, everyone seems friendly and professional. You’re learning and growing. Ostensibly, everything is going well.

Yet something isn’t right.

As time goes on, you realize that, as a person of color, you aren’t treated as well as many of your other colleagues. Subtle — and not-so-subtle — comments undermine your intelligence, exciting opportunities seems to slip through your fingers for no clear reason, and the energy just feels off. You’ve encountered this sort of bias before, but you’re disappointed that it continues to haunt you in a professional setting.

Most people of color experience this sort of discrimination, often in the form of microaggressions in the workplace. It can make you question yourself, damage your self-esteem and impede your progress as a professional — you deserve better. Here are a few ways to cope.

1. You have power.

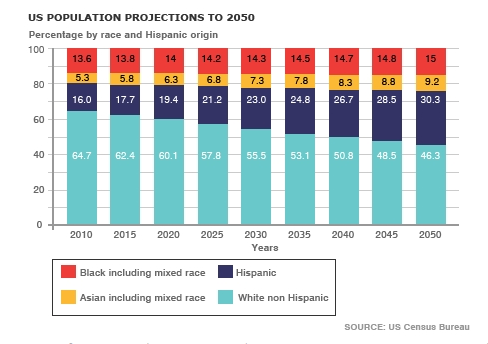

America’s demographics are changing rapidly, and there is strength in numbers: 43 percent of millennials are people of color, and each ensuing generation is even more diverse. Generation Z (born 1996–2010), the first members who are graduating from four-year colleges this year, is 47 percent Hispanic, African-American, Asian or multiracial. By about 2043, America will become a majority people of color nation, meaning more than half its population will be non-White.

In this context, it’s abundantly clear that you are not expendable! Companies that want to innovate and remain relevant must create a culture in which you thrive and feel a sense of belonging. Unite with your colleagues who understand this, and stand up for change. Any sensible employer will listen.

2. Understand the root of the problem.

I’m a White woman who grew up in an almost entirely White community. My parents and teachers taught me that racism is terrible, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was great, to be colorblind, and to never talk about race. They explained racial inequality like this: “We used to have terrible racism in our society, but then there was a civil rights movement, which was fantastic, and now opportunity is distributed equally. Some families — like ours — work hard, which is why we have our lifestyle. Other families choose not to work as hard, and that’s on them.”

I know my parents meant well, and they weren’t blatant racists by any stretch of the imagination. However, had I not worked for years in communities of color, this inaccurate and harmful way of thinking would still inform my understanding of racial inequality. Many White people in my social network share this mentality today.

Microaggressions will continue to occur until this mindset is uprooted from the workplace, a major — but doable — undertaking that must come from the top down. It’s up to CEOs to take the first step in creating a culture where everyone belongs.

A chief diversity officer, HR representative, or individual employee is unlikely to have the power to do this on his or her own. But, when someone approaches executives with a compendium of stories about how this harmful, inaccurate, and racist mindset is showing up in the workplace, he or she is likely to get their buy in to address it. Speak up-together.

3. Know your boundaries.

When microaggressions happen, don’t sweep them under the rug. While it should not be the oppressed’s job to educate the oppressor, when harm goes unaddressed, it keeps happening. So when an interaction at work makes you feel bad, waste no time wondering whether it was a microaggression. If it at all implied that you do not visually conform to someone’s expectation of who his or her colleagues are, it was.

This is why I recommend forming a “rapid response network” with colleagues who volunteer to intervene on the harmed party’s behalf. By bringing the harm to the aggressor’s attention and writing down what happened, you establish a narrative record of workplace discrimination that can be useful to the employees in making the case for change and to you if you later decide to take legal action against your employer. If, after an incident occurs, you feel comfortable approaching the aggressor yourself, ask him or her to meet privately. If you don't feel up to it yourself, ask one of your friends in the rapid response network to speak up on your behalf.

In a caring, neutral tone, say something like:

“You just said X/did Y. What were you thinking when you did/said that? Although you may not have intended it that way, your statement/action harmed me. I would like you to consider the impact of your statement/action, to apologize, and to work not to say/do something like that again.”

The first five times you provide this feedback, it will feel terrible and awkward. The next five times, you will feel stronger. Hopefully there will not be an eleventh time, because the culture will start to shift, and microaggressions will stop happening.

Image courtesy of Burst/Brodie Vissers.